At the tail end of March, researchers from the Southampton Institute for Arts and Humanities (SIAH) attended the Creative, Knowledge Cities (CKC) conference in Bristol. Held at Watershed, a cinema by the harbour, the event gathered academics, practitioners, activists and artists “to imagine an alternative to our current model of creative work.”

Attendees were preoccupied with doing, the verb-laden schedule calling on the multitudes of placing, consuming, commoning, valuing, designing, imagining, making, caring and structuring. During the two days, an assemblage of possible futures emerged; these challenged prevailing narratives of the creative industries, cultural sector growth, economic value and artistic appropriation.

At the conference, SIAH delivered a paper on “What Counts as Data,” drawing from research conducted during the AHRC-funded Feeling Towns project.

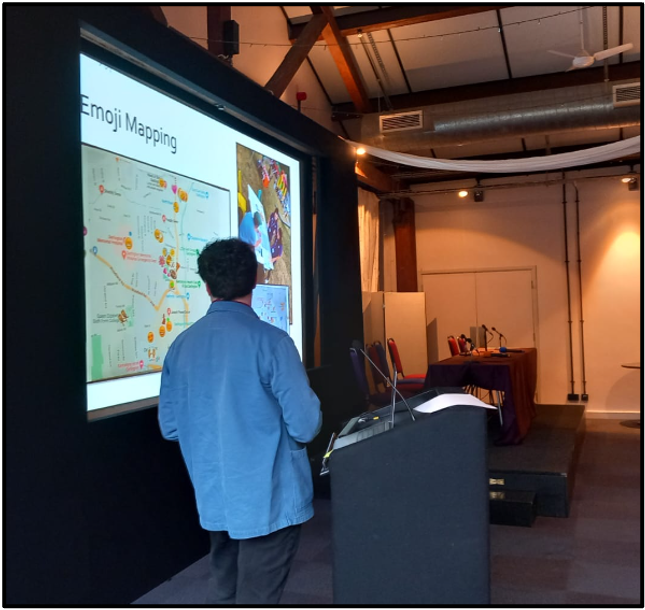

The presentation argued that creative methods—such as emoji mapping, photo elicitation, timeline drawing and poetry collage—can be used to understand the vagaries of people’s relationship to pride, place and belonging. It also advocated for the value and range of qualitative research, which can complement, challenge and complicate econometric data on culture, regeneration and local economies.

In the UK, the current government’s dominant framing of the relationship between culture and regeneration focuses on levelling up, but this relationship is not self-evident. Some claims require more consideration: one might be that City of Culture, for instance, has been an unequivocal success and should be built on as a model of funding for arts and culture.

“Restoring pride in place,” meanwhile, is a guiding mission of the 2022 Levelling Up White Paper, and appeals to emotion are now common in cultural policy and regeneration initiatives. We therefore sought to explore the complexities of place attachment, particularly its relationship to local pride, neighbourhood cultures and civic engagement.

The literature suggests that there are different kinds of pride that do different things: one widely-held distinction exists between authentic pride, which relishes genuine achievements that enhance social connections, and hubristic pride, which reveals a narcissism or egotism that erodes relationships and encourages competition.

Similarly, there are different scales for pride that potentially do different things: nationalistic pride can work in a very different way to civic or local pride, because one may enhance community activity and the other may inhibit it.

The methods used for Feeling Towns were intended to elicit the textures of people’s lived experience, often missing from government narratives about “pride in place,” which homogenise and make comparable distinctive visions of pride that exist in different communities.

These methods build on existing literature and were developed with Michael Howcroft, our resident human geographer, whose research on pride, shame and affect—as these relate to cultural regeneration—deeply informed this work. They include:

Emoji mapping creates living documents: open to interpretation and debate, where users can access instincts to work outside of convenient political geographies such as ward boundaries, which sometimes flatten or misrepresent complex community attachments.

Photo elicitation reveals uncertainty about nominal community assets and challenges the wider import of levelling up, which relies on the visibility of new physical infrastructure to obscure more than a decade of austerity, creating conditions that have frayed the social and emotional bonds within communities.

Timeline drawing provides the chronological development of people’s views and feelings, showing how ambivalent feelings can complicate cogent community narratives: these responses often exceed and undercut policy aspirations and populist political language.

Poetry collage focuses on language and form, which encourages people to articulate different ideas about the nature of place. Ordering single sentiments into collage is not an act of simple coherence; rather, it incites a necessary assembly of dissonance and contradiction.

These creative methods bring into relief both the product and the process, which suggests their usefulness as artefacts of consultation for communities, but also as contributions to wider thinking on what stories of place are supposed to do and what narratives of regeneration intend to capture.